By the late 1700s, the mayor of Paris wanted to end Carnival and ban King Cake!

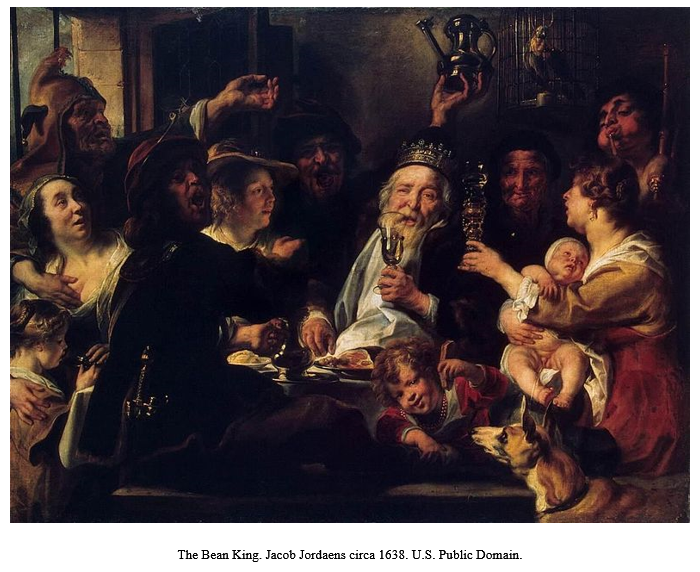

As early as the 14th century, historians have found documented evidence to show revelers baked King Cakes to celebrate the winter solstice. And the fève or fava bean hidden inside was associated with bringing good luck for fertility, or a bountiful harvest, and more. The holiday became quite popular across Europe and whomever found the bean, or fève, became the king or queen for the day. There was dancing in the street, lots of drinking, and other raucous behavior that accompanied the celebrations. This provided the lowest levels of society temporary relief from societal pressures imposed by the ruling class. And in the 16th century, French bakeries (boulangeries) and pastry shops (pâtisseries) both wanted the sole right to sell the cake. It was up to the king to decide.

As Christianity spread across Europe, the church prohibited the pagan festival and the worship of non-Christian gods. To assure this happened, the church influenced their followers to celebrate Three Kings’ Day or the Epiphany on January 6th which coincided with the winter solstice. And like the three wise men, Christians would celebrate and recognize the divinity of the baby Jesus. However, the fun, festivities and cake remained popular.

In fact, in France, there was a king cake war because the cake was so popular. So who won? What establishment did the king pick to make and sell their official kings’ cake, the boulangeries or pâtisseries?

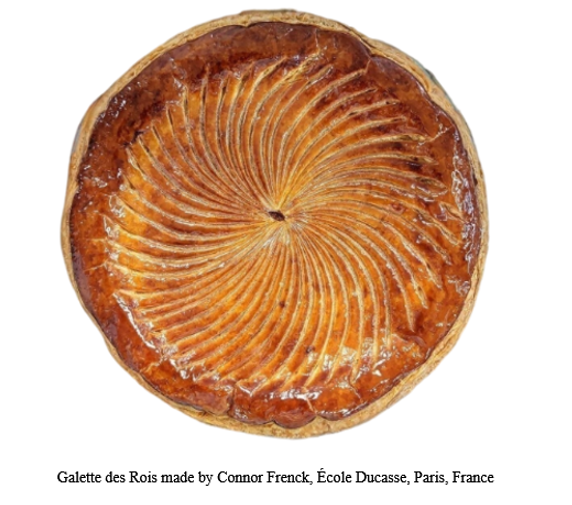

Interestingly, even today, who can sell what—and where there—remains a matter of French law! You see, there’s a difference between a boulangerie and a pâtisserie. My son is in his third year at École Ducasse in Paris studying French Pastry Arts and he enjoys viennoiserie, which is like blending pastry and bread-making, but that’s a whole other topic. A boulangerie specializes in bread and other baked goods, whereas a pâtisserie sells pastries. That’s a very simplistic explanation. It’s far more complicated!

The king’s edict of 1794 granted pastry chefs the monopoly to make the Gâteau des Rois. This ring-shaped gâteau was made of a brioche with a dough using yeast.

How did the boulangers respond?

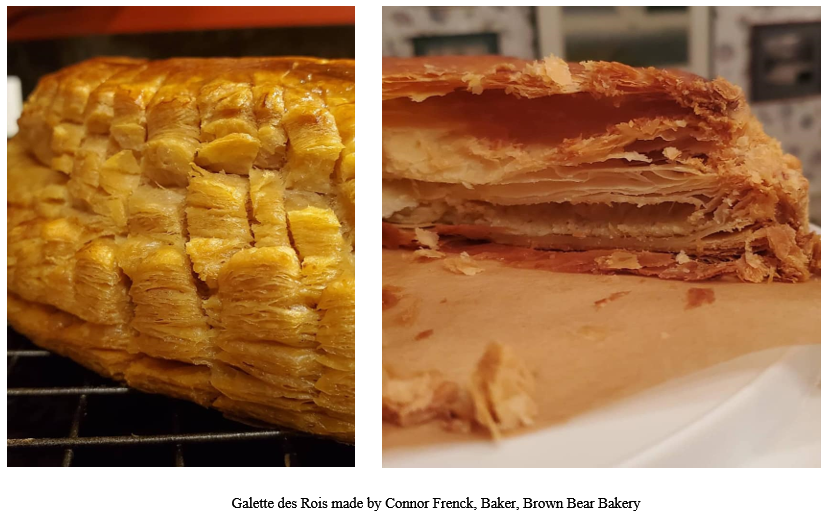

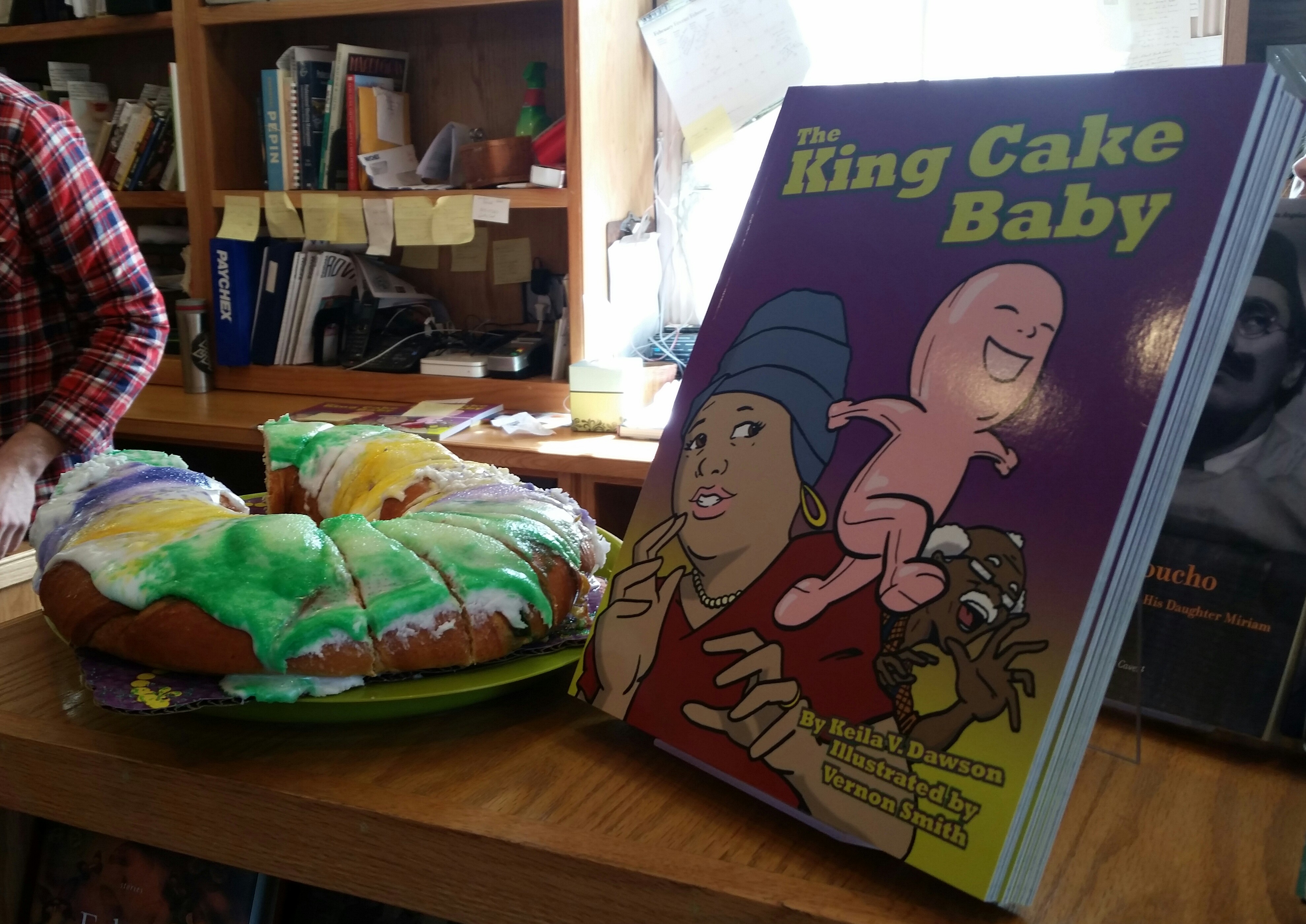

The bakers couldn’t sell the ring-shaped cake, so they created something new. They made Galette des Rois with a puff pastry in the shape of a pie! This Kings’ Cake has multiple thin layers filled with frangipane, an almond paste. And yes, a fève is hidden inside. Today, instead of a bean, there’s a trinket of some kind, perhaps a tiny porcelain or plastic figurine.

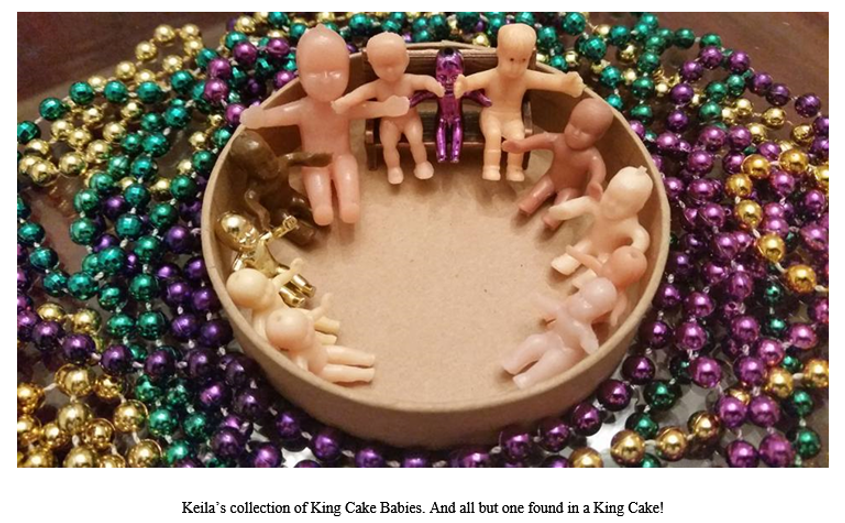

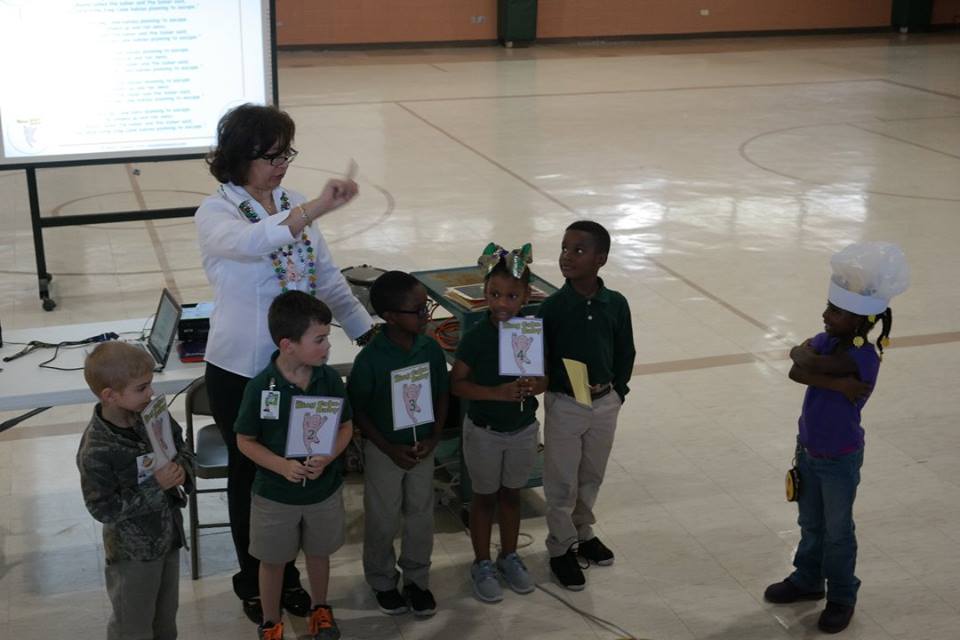

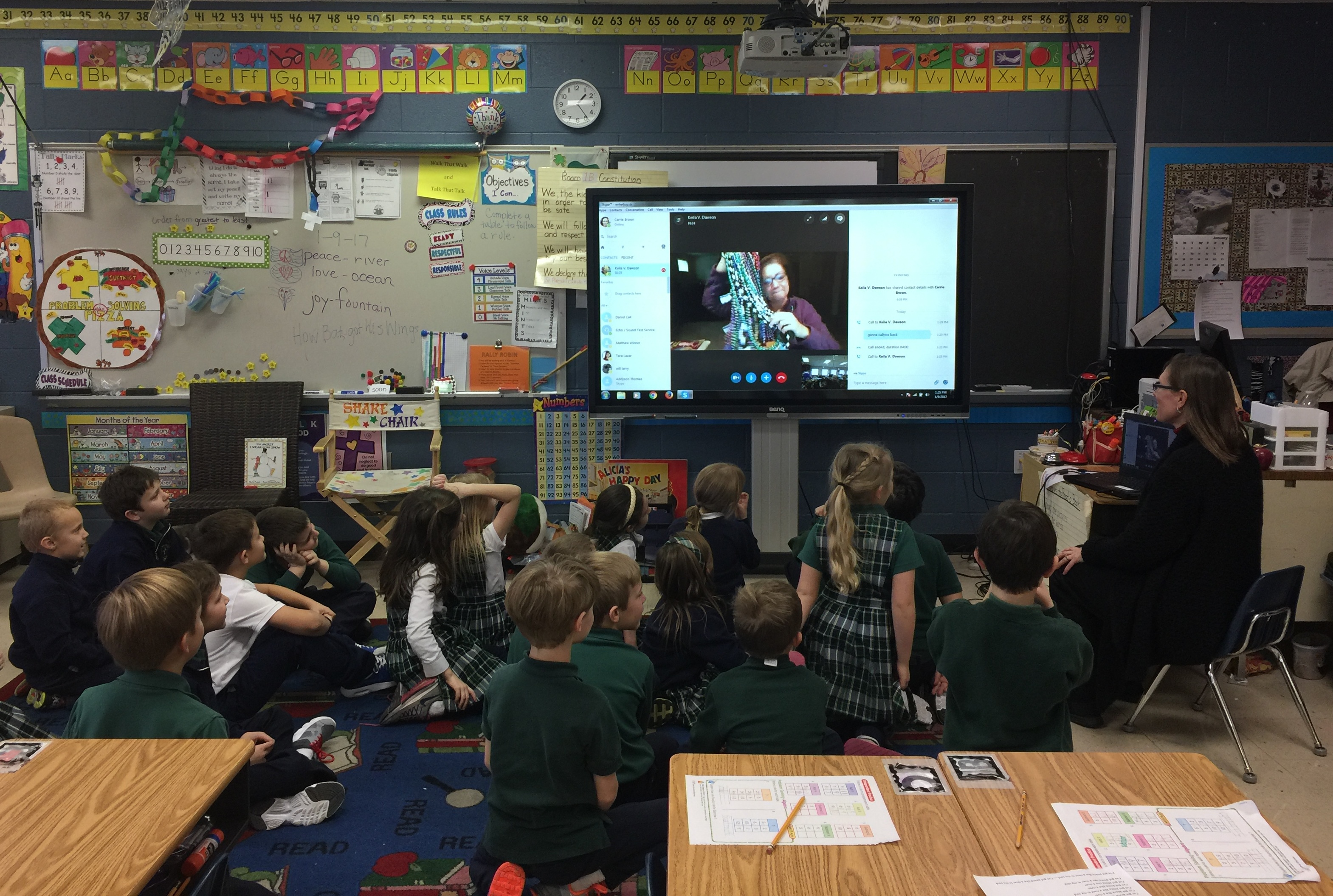

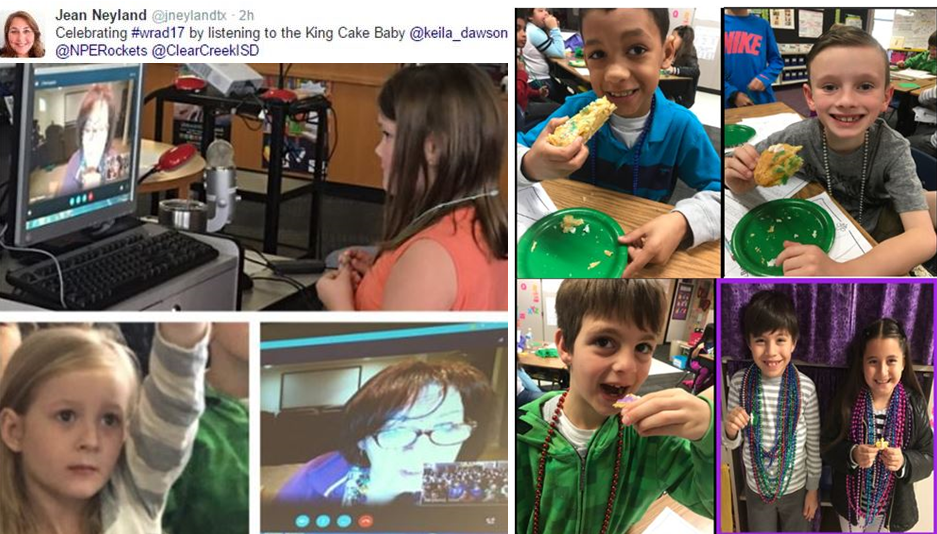

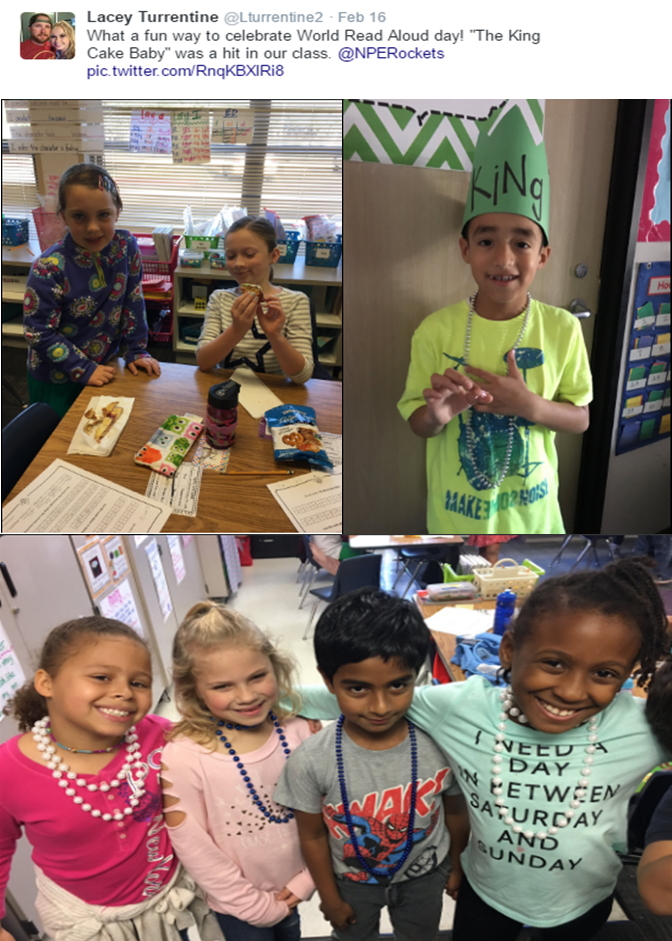

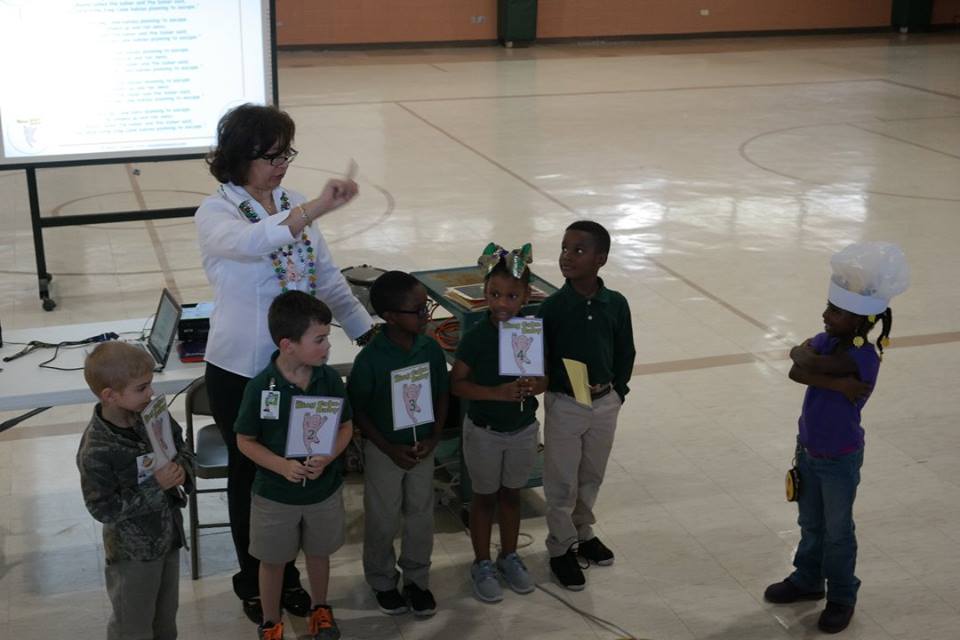

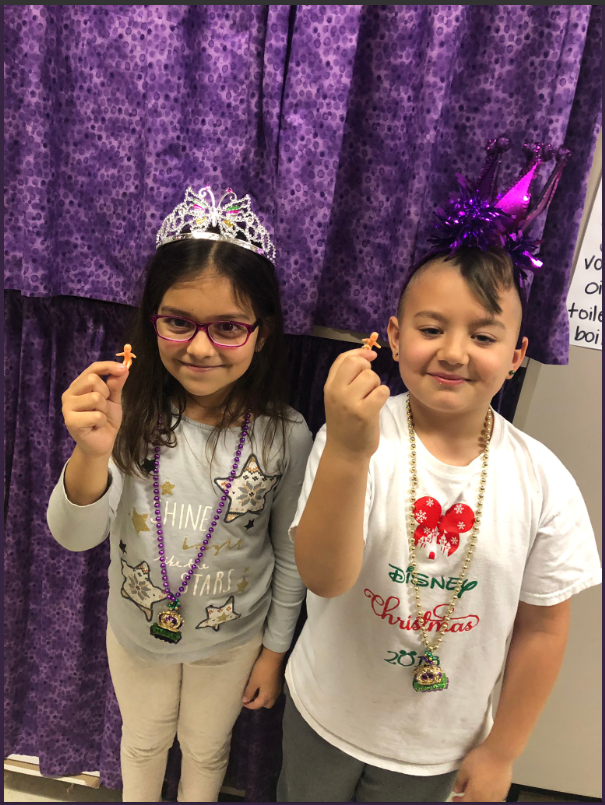

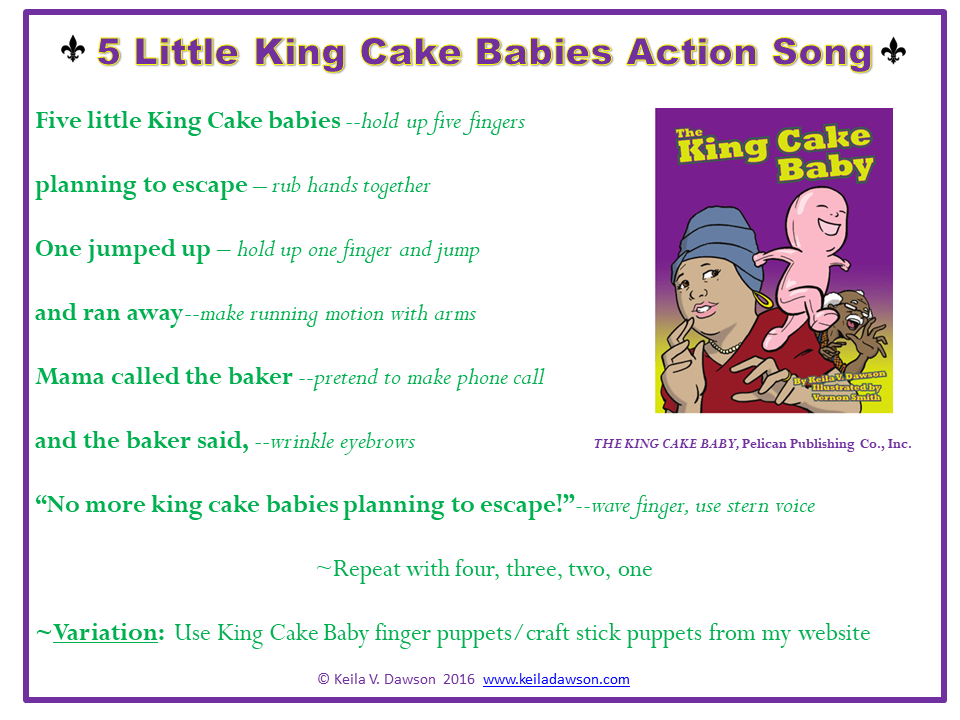

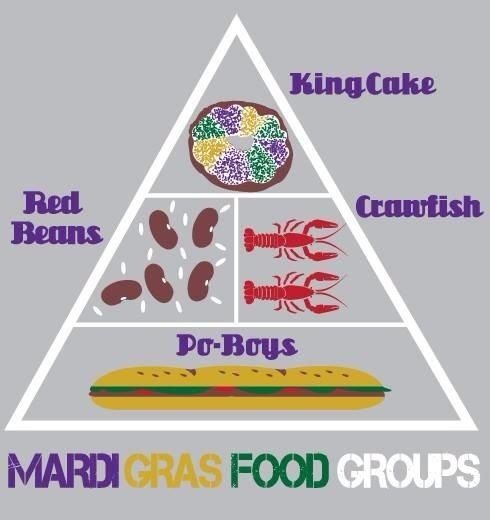

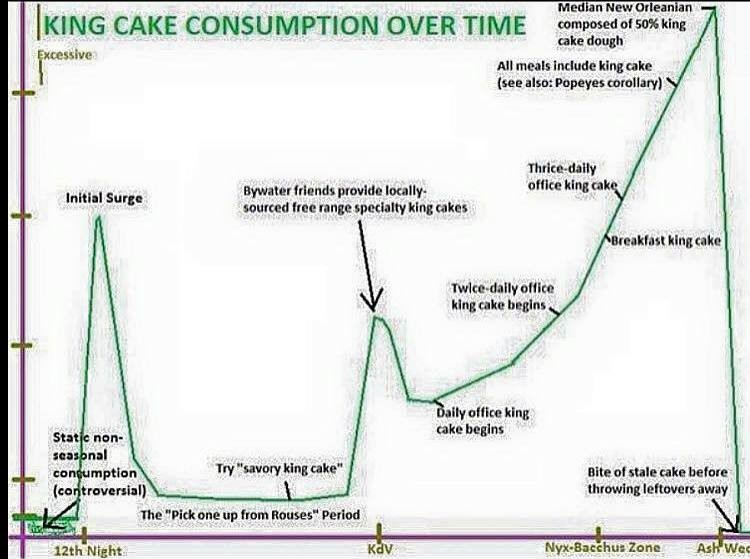

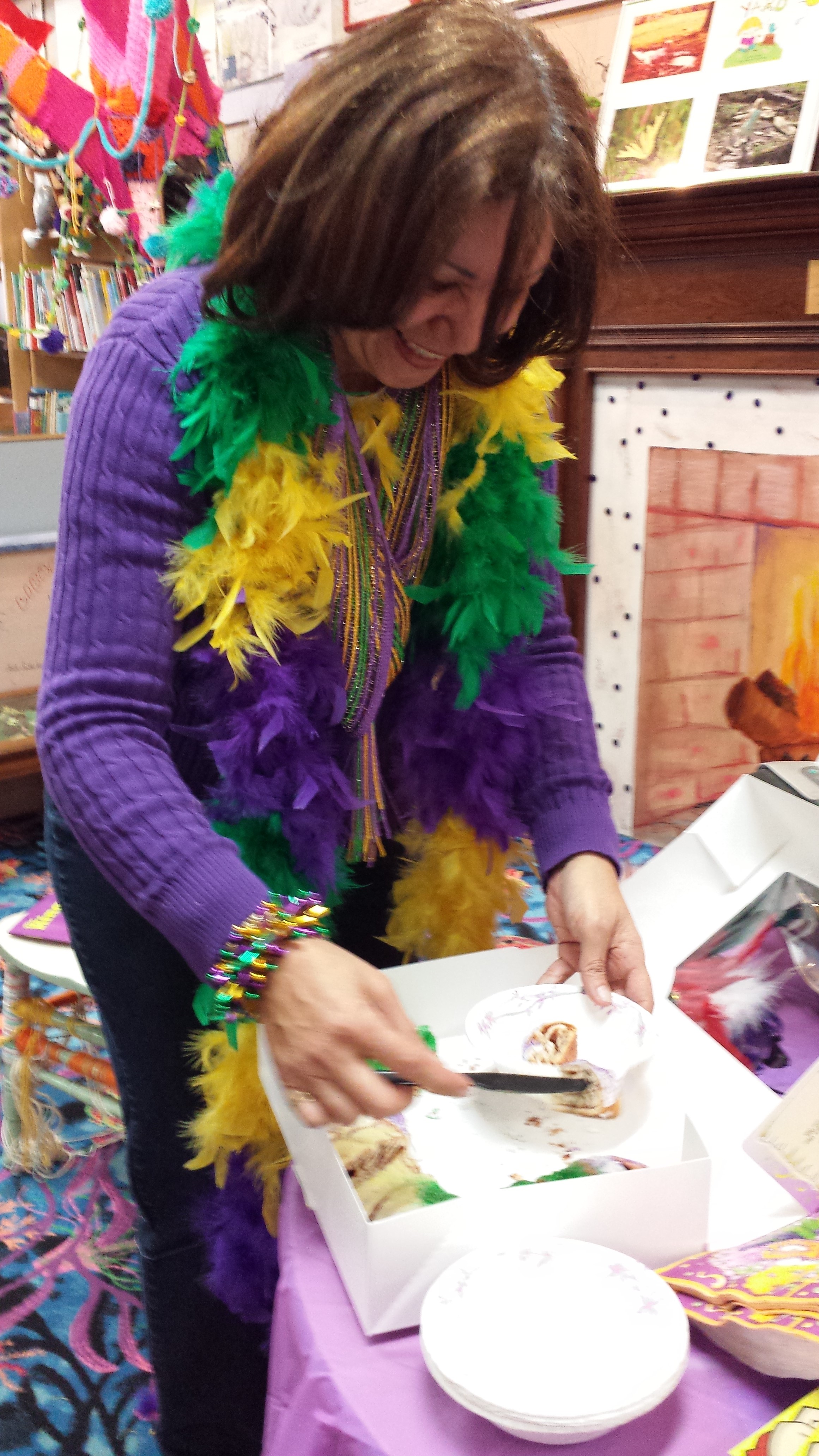

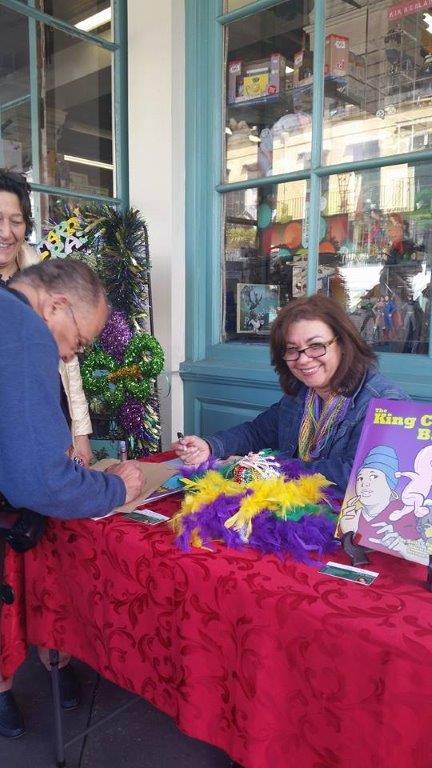

Fast forward to Louisiana, once a French colony, where the cake tradition continues. In France, King Cakes are sold from January 6th throughout the month of January. In Louisiana, the first King Cake appears on the same date, kicking off the Carnival season. But there, they are consumed until Mardi Gras Day—Fat Tuesday. The King Cake baby is the most popular fève hidden in Louisiana King Cakes. And the baby comes in many sizes and colors.

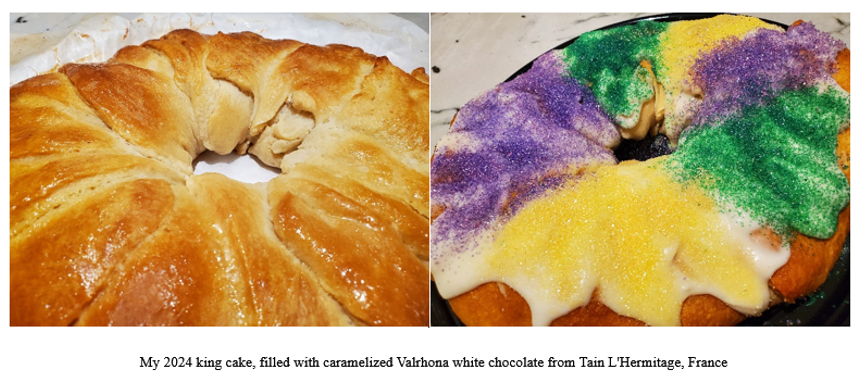

I’ve had my share of King Cake varieties from different bakeries over the years and I continue to experiment with making my own. This year’s Epiphany cake was filled with Valrhona chocolate from Tain L’Hermitage, that my son brought home and caramelized for me.

Whether you prefer a Galette des Rois, Gâteau des Rois, or a variety of the Louisiana King Cake, you have until February 13, 2024, Mardi Gras Day, to eat your share. And if you’re lucky, maybe you’ll find the fève!

Happy Mardi Gras!